Active

Popular

Climate Change and Conservation

Pru Allison

Pru Allison

March 27, 2024

March 27, 2024

“We are the first generation to feel the impact of climate change and the last generation that can do something about it.” – Barack Obama

For many of us the reliability of the seasons is changing, and there’s work to be done if we’re to adapt. Certainly the effects of climate change are becoming increasingly evident, and as part of our commitment to environmental conservation we’re hard at work to support the research being done on the ground. One such project is the Impacts Of Surface Water On Herbivore Ecology And Socio-Ecological Knock-On Effects. We’ll concede it’s not the snappiest name but the work being done is so worthy that we’re willing to overlook its wordy moniker.

Climate change has made itself apparent in Botswana through soaring temperatures and decreasing rainfall. While climate variability was already a part of this arid landscape, it’s the consistent movement towards extremes that’s concerning. The outcome of this is likely to be a reduced availability of natural surface water – water that’s crucial in sustaining wildlife. The surface water project will study the available surface water in the Makgadikgadi Pans and its impact on the ecosystem.

You might well be familiar with our lodges in the Makgadikgadi Pans: Jack’s Camp, San Camp, Camp Kalahari, Meno a Kwena and Planet Baobab. The allure of these properties lies in the otherworldy surroundings of the Makgadikgadi – a network of salt pans that once formed a super lake in the midst of the Kalahari Desert.

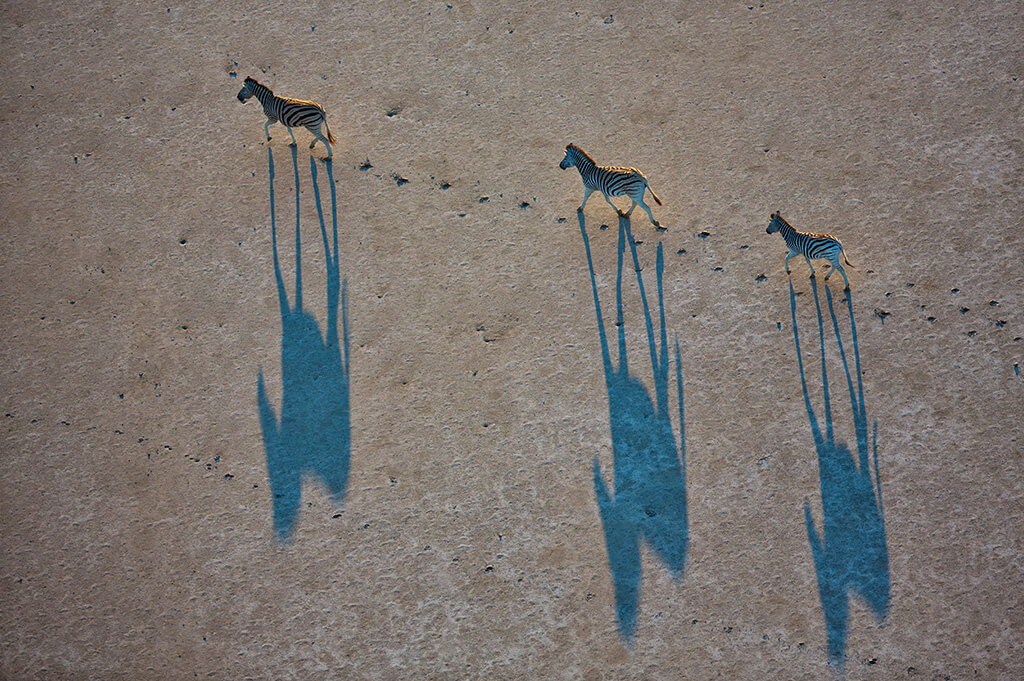

This shimmering desert expanse has captured many a heart and inspired cinema, literature and art. It’s home to the Zu/’hoasi bushmen and women, and hosts a significant portion of Africa’s second largest migration in which a spectacle of 30,000 zebra and wildebeest traverse Northern Botswana.

As with the rest of the planet, change is afoot here too, specifically concerning surface water availability which has been affected by two different phenomena. The first of these is the fact that the Boteti River – above which Meno a Kwena sits, began flowing again back in 2009 having been dry for 19 years. Secondly, over to the Eastern side of the region, an artificial water supply has been in place for the past decade.

At the height of the dry season the ephemeral Boteti River is flooded, but over recent years its flow has slowed down prompting concerns that it might dry up once again. Little is currently known about the impacts of surface water availability, nor the different types of water sources in the area. What is known for sure is that the availability of surface water has both direct and indirect consequences on semi-arid ecosystems so it’s important that research is undertaken to determine its impact in the Makgadikgadi Pans. In particular, the project will look at the effect on the ecology of large herbivores and the knock-on effects on vegetation, landscape-scale connectivity and human-elephant conflict.

The study aims to investigate these impacts and then use the data gathered to advise on where best to position artificial waterholes, and how far apart they should be from one another, as well as the timing and volume of outputs, while minimising any detrimental effects. The field of conservation is having to adapt to stay abreast of climate change and this work will do just that while also tracking fluctuations of water availability.

“It’s no longer possible to study any species, habitat or ecosystem without considering climate change,” explains our Director of Conservation Dr Jennifer Lalley. “It now competes with habitat loss as the main driver of species extinction. But where habitat loss was combatable at a local scale, climate change is out of the hands of the local conservationist. It’s up to our global community to change it. What we can do is try to mitigate the impacts as best we can.”

Beyond this, the results will also help us identify and map the network of elephant trails through the area, which will in turn help mitigate human-wildlife conflict and allow us to ensure maintenance of landscape-scale connectivity (landscape-scale is a holistic approach to landscape management that aims to reconcile competing objectives.)

The researcher on the project is PhD student of the Okavango Research Institute of the University of Botswana Delphine Dubray. She will be following some specific methodology to reach the key objectives of the study.

The water quality of the water holes will be analysed four times a year, while camera traps will be in place throughout the year to monitor the activity of large herbivores at the water. This will help us gain a clearer understanding of how these species which could include elephant, giraffe, zebra and wildebeest, use the water holes and how that usage is affected by the quality and availability of the water.

In addition to this, surveys of the area’s vegetation will be carried out. Satellite images and indices will be analysed and habitat maps will be updated and compared with formerly established maps. From this we’ll be able to determine the seasonal and historical changes in vegetation characteristics around water sources depending on their use and particularly how they’re used by elephants.

Furthermore, the project will look at data from collared adult bull elephants to ascertain their movements across different distances. We’ll also use camera traps to study the local use and landscape-scale connectivity between distant areas of permanent water for different species. Elephant trails will be mapped through collar data, satellite imagery and direct observations.

Finally, questionnaires will be distributed to those who live in the local area to help us investigate the impact that artificial water provision has on human-elephant conflict.

“Artificial water provision is often considered as a way to mitigate drought and human-wildlife conflict,” notes Delphine. “But the true consequences of such strategies have not been assessed.”

The project forms an important component of our Large Mammal Migration conservation work in the Kalahari which you can learn more about here and also synergises with the Elephants For Africa collaring project we support.

Climate change will continue to create complexities in the world of conservation, complexities that must be addressed through projects like this. Conservation is in our DNA, and we and the work we do, will continue to adapt accordingly.

Special Offers

Our special offers are designed to help you experience everything southern Africa has to offer whilst also saving some all-important pennies. Whether you’re about to embark on a once-in-a-lifetime solo trip, or are celebrating a special occasion, have a peek at our offers and see what could be in store for you.